Given the enormity of the legislation surrounding health & safety it is no small wonder there is confusion in its interpretation. Furthermore, the major change, self regulation, which the H&S Work Acts introduced in 1974, has never been fully embraced by the construction industry. Alistair Moffat considers working at height.

Given the enormity of the legislation surrounding health & safety it is no small wonder there is confusion in its interpretation. Furthermore, the major change, self regulation, which the H&S Work Acts introduced in 1974, has never been fully embraced by the construction industry. Alistair Moffat considers working at height.

‘Fall, fall, arrest’: I am quoted prescriptive distances or testing at specific intervals from legislation which has long been removed from the statute books. The commonly held belief that no fall protection is necessary below two metres no longer applies, and hasn’t since the introduction of the working at height regulation in 2005.

Regrettably much of this culture is fuelled by the lack of understanding of the underlying principles of H&S. Many companies only train managers and supervisors to a very basic level (SMSTS or SSSTS). In order to satisfy their legal requirement to seek competent advice (Reg 7 MHSW) they employ an H&S consultant. This principle exists with many principal contractors (PCs) who have limited H&S competence on site but have roaming H&S advisers. In my experience, these advisers only highlight non-conformance, promulgate damning reports and vanish. Hence their contribution is only to police, not improve. Moreover the reports stemming from their visits have a bias to highlighting shortfalls in subcontractors often turning a blind eye to the poor H&S culture of the PC concerned.

Last month I was invited to a pre-start meeting representing a drylining subcontractor. The scope of work included the construction of lightweight steel frame (LSF) and cement board between the concrete slabs. During the site walkabout the PC announced the scaffolding as agreed would not be constructed by the start date. Thus the onus of providing a safe system of working at height was thereby transferred to the drylining subcontractor. There was much dialogue over commercial issues as contractually any edge protection was to be provided by the PC. The PC then dictated that the operatives were to work from a fall restraint system using a ‘man anchor system’ (often referred to as a ‘crucifix’).

As soon as I engaged in conversation with the PC it was clear he had very limited understanding of the differences between ‘fall arrest’ and ‘fall restraint’. The site in question had nine levels and was bordered by two railway lines into central London. Furthermore in midsummer wind gusting through the higher levels will result in a hazard of materials blowing onto to track which was unacceptable. Scaffolding and debris netting would have created a far safer working environment and provided ‘collective’ fall protection.

I would not agree to the use of fall restraint as the operatives were working too near to the edge. My concerns were driven by a visit to a similar site where LSF was being installed (without scaffolding) using fall restraint on crucifixes. The physical effort of moving the ‘crucifix’ around the slab had subjected the operatives to excessive manual handling (as component parts weigh some 100kg). Plus with having to unclip to cut LSF or get materials (fall restraint lanyards are only two metres long) they failed to clip back on and were ‘carded’ for noncompliance. More importantly they were circumventing a system that was too cumbersome in practice and putting themselves and others in danger. A critical element of any PPE is ease of use. Regarding the said site I agreed to use a fall arrest system using inertia reel from the columns.

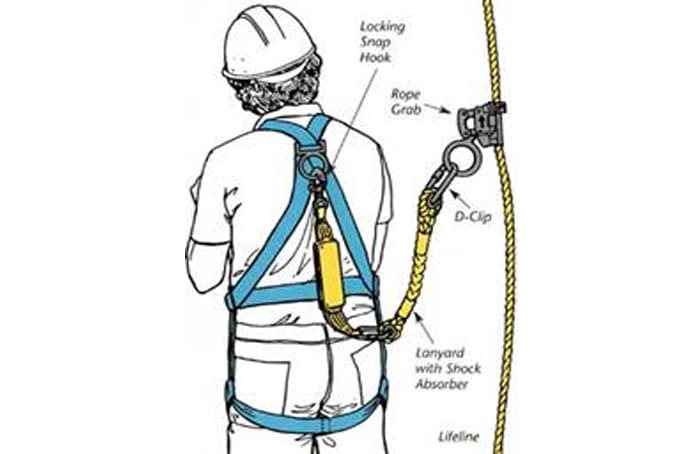

A point of clarity – a fall restraint system prevents (and creates awareness of ) an operative getting near an exposed edge. All component parts should comply with EN 354/EN358. It should be noted that operatives should wear a belt with a ‘D’ ring positioned at waist level on rear. Note that for fall restraint a full body harness is not necessary although can be used if attachment points are appropriately positioned. For fall arrest a full harness shall always be worn. If there is any doubt as to whether an operative is working in a restraint or fall arrest situation the latter should always be worn.

A fall arrest system is far more complicated and costly. Anchor points must be tested to BS EN 795 and periodically inspected. Operatives must receive formal working at height training. Harnesses, lanyards and work position devices must be subjected to an inspection regime (PPE Directive 89/686/EEC). Furthermore, there will be potential injuries as a consequence of a fall arrest system and there must be system in place to recover an operative if he falls and appropriate medical care must be available.

All of the above are to be underpinned by a fully developed safe system of work. Common failings are using fall arrest system where there is insufficient distance for the system to deploy (normally requires six metres). Most off the shelf harness are limited to 100kg (16st). Many operatives who are physically large (but not overweight) exceed this limit.

In summary, the hierarchy of risk control is to remove the hazard. Hence ‘collective protection’ of fixed scaffolding with debris netting will result in a less hazardous workplace and negates the need for a whole raft of risk assessment and subsequent controls, some of which are costly to introduce and maintain – so where we can, why don’t we use it every time?

Alistair Moffat

Brunel Construction Consultants

T: 0208 300 0090